Biotechnology from the Blue Flower

Artists Anna Dumitriu and Alex May are working with CHIC Consortium members to develop a new sculptural and bio-digital installation entitled “Biotechnology from the Blue Flower” and will be spending time on site with consortium members over the life of the project. In 2019 the artists attended the consortium meeting in Madrid and have been working with chicory roots in their studio, and in February 2020 they will be visiting Wageningen Plant Research, Sensus and KeyGene as part of their research with more visits to come.

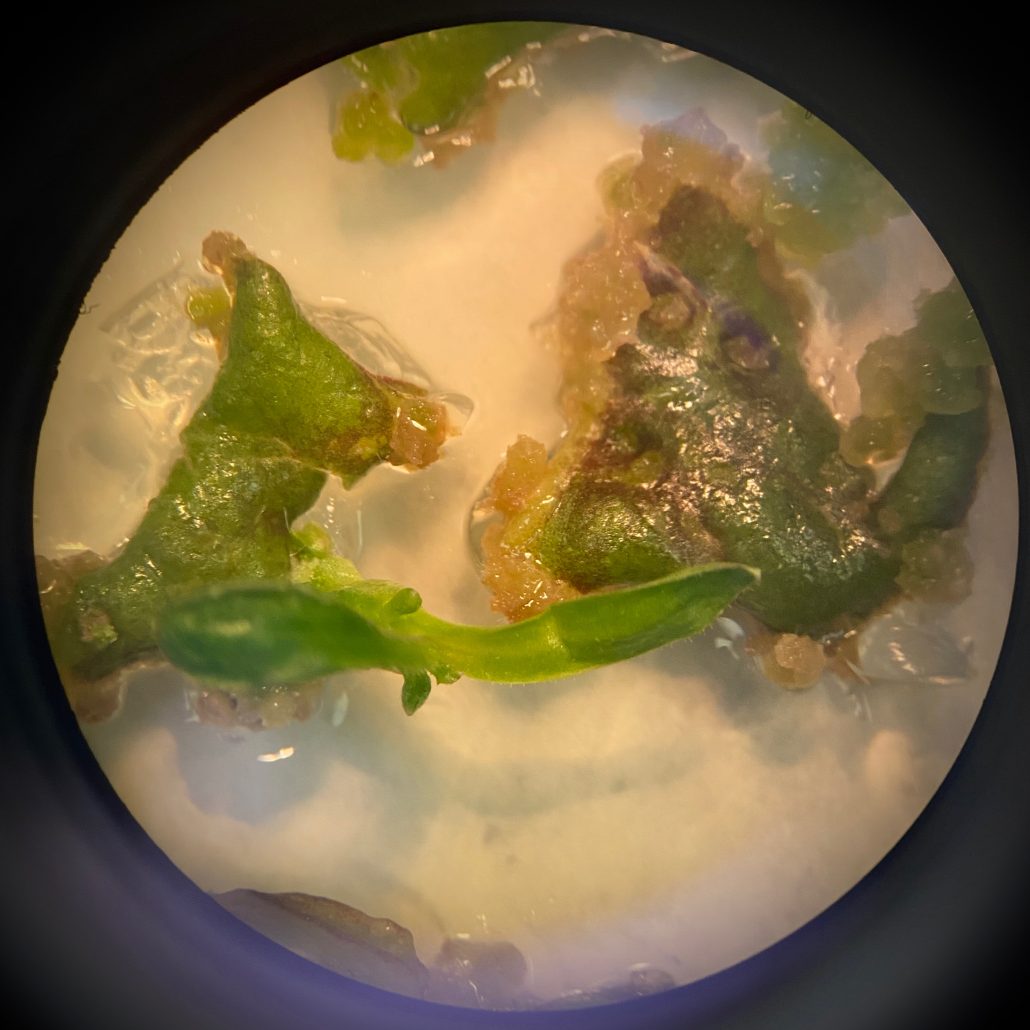

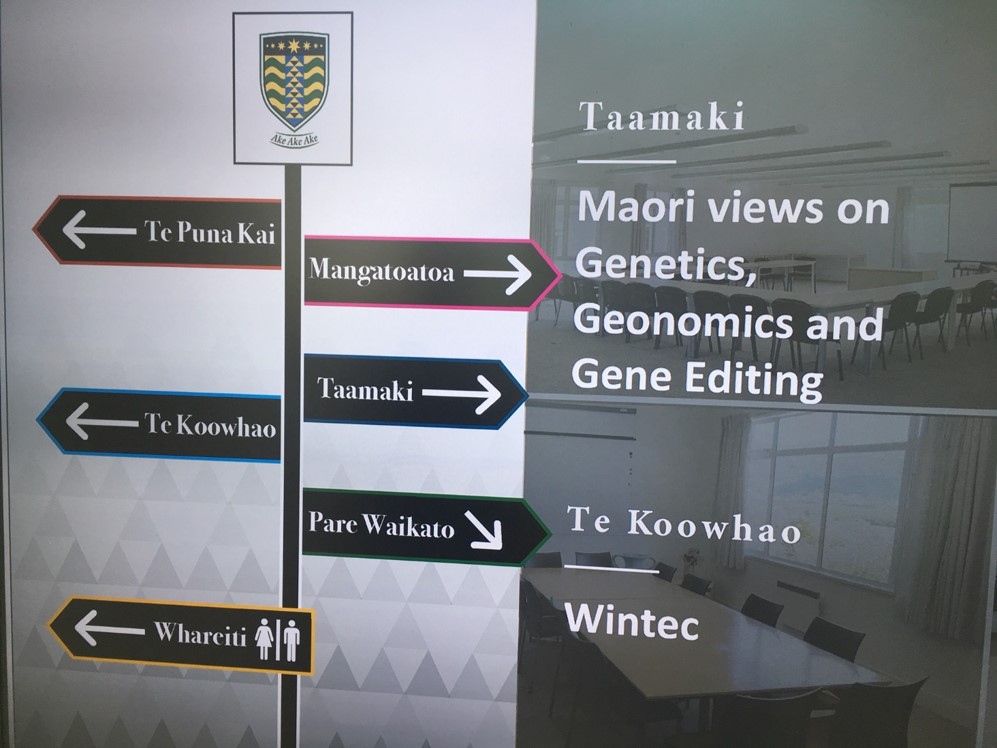

Dumitriu and May are exploring the internal and external morphology of chicory plants and well as the history and cultural impacts of the plants throughout history, for example as an ancient remedy, a natural dye, or a coffee additive in times of crisis and they aim to make links between those earlier histories and the cutting edge contemporary research being explored today by the CHIC Consortium, especially and the potential future benefits of working with new plant breeding methods techniques such as CRISPR to provide future healthcare and food security benefits.

Chicory was one of the plants (along with the cornflower) that inspired the idea of the Blue Flower in German Romanticism – a central symbol of the movement. The romantic movement was in part a reaction to the industrial revolution and held nature and emotion in high esteem. The artists told us “we feel that we are now experiencing a biotechnological revolution and it’s fascinating again this idea of the blue flower becomes an important symbol again, but this time in a more complex position at the interface of nature and technology. Central to societal explorations of what may be acceptable in terms of synthetic biology and how ‘nature’ and ‘natural’ may be defined in the future.”

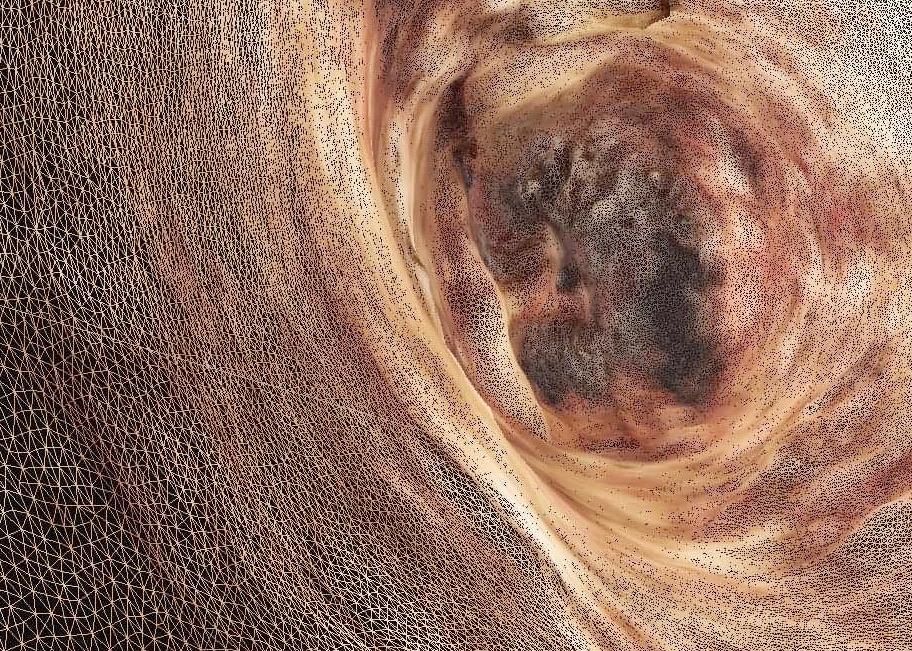

The artists are focussing on the areas of the use of chicory for dietary fibre and its impact on human health and the human microbiome, antibiotics, and the uses of inulin and medicinal terpenes extracted from Cichorium intybus (common chicory). They are working with the plants themselves: the roots, the flowers, chicory flour and chicory inulin and terpenes, as well as other potential materials they might discover. These sculptural, physical materials will be fused with video footage from the laboratory and data visualisations derived from the research processed through 3D scanning and modelling techniques to create a final installation with outcomes being developed throughout the life of the project. The artists are especially keen to work with CRISPR, as a development to Anna Dumitriu’s earlier works with synthetic biology, such as “Make Do and Mend”, which the CRISPR Journal described as “Perhaps the First Application of CRISPR gene editing technology in BioArt” Keep up to date with the artists at www.annadumitriu.co.uk and www.alexmayarts.co.uk

This project has received funding from the EU Horizon 2020 research & innovation programme under grant agreement N. 760891.

This project has received funding from the EU Horizon 2020 research & innovation programme under grant agreement N. 760891.